The Ultimate Negotiation Strategy: How Senior Leaders Orchestrate Three‑Dimensional Deals

In complex, multi‑party deals, the biggest risk is not losing the negotiation—it is losing control of the system you are negotiating in. High‑stakes RFPs, price increases, strategic alliances, and M&A conversations succeed when leaders can see the complete landscape and design for what comes next, not when they hope their first plan survives contact with reality.

This article introduces a practical architecture for what can be called three‑dimensional negotiation: a way to design the people, power, and process around your deal so that your chosen tactics actually work under pressure.

Who this playbook is for

Senior executives, sales and business development leaders, and procurement professionals all face a similar pattern:

- The number of stakeholders keeps growing.

- The stakes of each decision keep rising.

- Traditional one‑to‑one playbooks no longer explain why deals stall, implode, or turn toxic.

If you are running or sponsoring negotiations that involve boards, regulators, unions, customers, suppliers, and internal operators at the same time, this framework is designed for you.

It does not replace the fundamentals of questioning, framing, or concession planning; it sits above them, providing a strategic system within which those skills can be deployed safely.

The core idea: asking “what comes next?”

Most leaders still treat “strategy” as the plan for how they want the negotiation to go. Professional negotiators define strategy differently: it is the discipline of asking “What comes next?” at every stage.

This is not pessimism; it is proactive design. It means identifying gaps and opportunities before they become crises, assessing power so you can maximize and preserve it, and turning potential failure into structured success.

In three‑dimensional negotiations:

- Power is distributed across multiple parties.

- Outcomes are interdependent across functions and organizations.

- Timing often matters more than individual terms.

A strategy that cannot answer “what comes next?” is not a strategy; it is an opening script. The framework below exists to give leaders the visibility and control they need when preferred approaches meet unexpected resistance.

The basic model: People, Power, Process

At the foundation of every robust negotiation strategy is a simple but non‑negotiable model: People–Power–Process.

Strategic negotiation model, people, power, and the process

Figure: The People–Power–Process model – the foundational inputs for three‑dimensional negotiation strategy.

People: the human system

The “People” component is not an org chart or a CRM export. It is a role‑based map of everyone whose behavior can move the outcome, including:

- Decision makers, influencers, implementers, and blockers on each side.

- Internal stakeholders who can quietly veto or slow‑roll execution.

- External actors such as regulators, unions, partners, or boards.

In large programs or price‑increase campaigns, you are not listing names; you are mapping archetypes—for example “Regional VP “, “Operations director “, “Account Manager”, etc.

This map exists for one reason: if the negotiation needs to escalate or shift direction, you must know who can talk to whom, and where movement will stall because no relationship exists.

Power: potential energy, not force

Power in this model is not aggression; it is potential energy. It is the collection of conditions that make a chosen negotiating style sustainable, such as:

- The alternatives each side has (their BATNA).

- Their dependence on your solution or relationship.

- Information asymmetry in your favor.

- Time pressure, standards, and legitimacy you can lean on.

A crucial insight is that power behaves more like physics than politics: once you convert it into action—a threat, a demand, a non‑negotiable ultimatum—it moves from potential to kinetic and flows from one side to the other side with every action or inaction.

Using power always has a cost. Strategic leaders design negotiations to preserve and enhance as much potential power as possible, and to convert it sparingly and deliberately.

Process: the control system

Process is not bureaucracy or a rigid checklist; it is the control system that governs when and how power is deployed through people.

Well‑designed process answers questions such as:

- In what sequence will conversations happen?

- Who is allowed to commit to what, and when?

- What are the rules of engagement for question, proposals, meetings, or escalation?

In complex deals, process is what stops an enthusiastic executive from firing off a threat on a call that destroys six months of carefully accumulated leverage.

The Wheel of Negotiation: five execution styles

Once the People–Power–Process foundation is set, the next tool is the Wheel of Negotiation, which describes five distinct styles of conducting the negotiation itself.

Figure: The Wheel of Negotiation – five execution styles from transactional to relational

Each segment of the wheel reflects a different posture, meeting design, questioning style, and proposal structure along a spectrum from highly transactional to deeply relational.

| Wheel Segment | Core Nature | Typical Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Auction | One‑to‑many, hyper‑competitive, price‑driven | Reverse auctions, competitive tenders, highly substitutable offers |

| Hard Bargaining | Positional, leverage‑driven, often zero‑sum | One‑off deals, distressed sales, end‑of‑quarter push |

| Concession Trading | Structured give‑get, explicit trades | Contract clean‑ups, scope adjustments, service‑level tweaks |

| Win‑Win | Collaborative, interest‑based, joint problem solving | Long‑term partnerships, complex service agreements |

| High Dependency | Deeply relational, creative, mutual reliance | Joint ventures, union negotiations, strategic alliances |

Moving clockwise around the wheel, negotiations become more complex, more relational, and less about pure price. Price is still a variable, but it no longer explains the deal on its own.

The wheel governs behavioral execution:

- How you structure questions.

- How you frame proposals.

- How meetings are run and in what sequence.

- How you frame value, risk, and trade‑offs.

Crucially, the wheel is not strategy. It is the set of tactics and behaviors you employ once a strategy has been chosen and resourced.

The six power phases: the 6 Cs

The bridge between People–Power–Process and the Wheel is a second model: the Power Phases, known as the 6 Cs.

Strategic Negotiation Power Graph

Figure: The 6 Cs – Power Phases from low to high power requirement

These six phases describe the amount and type of power required to sustain a given approach:

- Concede – Lowest power. You accept their terms to preserve the relationship or avoid greater harm.

- Collaborate – You have enough power to co‑design outcomes but not to dictate them. Power tends to be equal across the parties involved.

- Compromise – You trade structured concessions to reach an acceptable middle ground.

- Capture – You have sufficient leverage to extract value assertively without destroying the relationship.

- Compel – You control the process and can dictate terms, often via auctions or hard constraints.

- Cease – You walk away. This is the ultimate expression of power: the credible ability not to do the deal at all.

Graphically, these phases climb in power as they move from Concede up toward Compel and Cease. The colors match the wheel segments, visually reinforcing that each power phase enables or constrains certain styles of execution.

Cease does not appear on the wheel because it is not a style; it is a decision. The capacity to cease is the boundary condition that gives every other phase meaning.

How the models fit together

With both models on the table, the hierarchy becomes straightforward:

- People–Power–Process – Raw strategic inputs.

- 6 Cs Power Phases – Strategic posture and escalation design.

- Wheel of Negotiation – Executional style and behavior.

Put simply:

- The People–Power–Process model defines what you have to work with.

- The 6 Cs define how much power you can credibly use, and in what posture. Defines which styles you can execute effectively.

- The wheel defines how you behave once those conditions are in place.

Most negotiation failures in high‑stakes environments can be traced to a single pattern: teams choose a style on the wheel—”let’s collaborate,” “let’s push hard,” “let’s run an auction”—without first ensuring they have the power to sustain that style.

The result is predictable:

- “Win‑win” collapses into endless compromise.

- Hard bargaining triggers backlash and reputational damage.

- Auctions implode when suppliers realize the buyer cannot actually walk away.

The models above exist to prevent those errors before the first meeting.

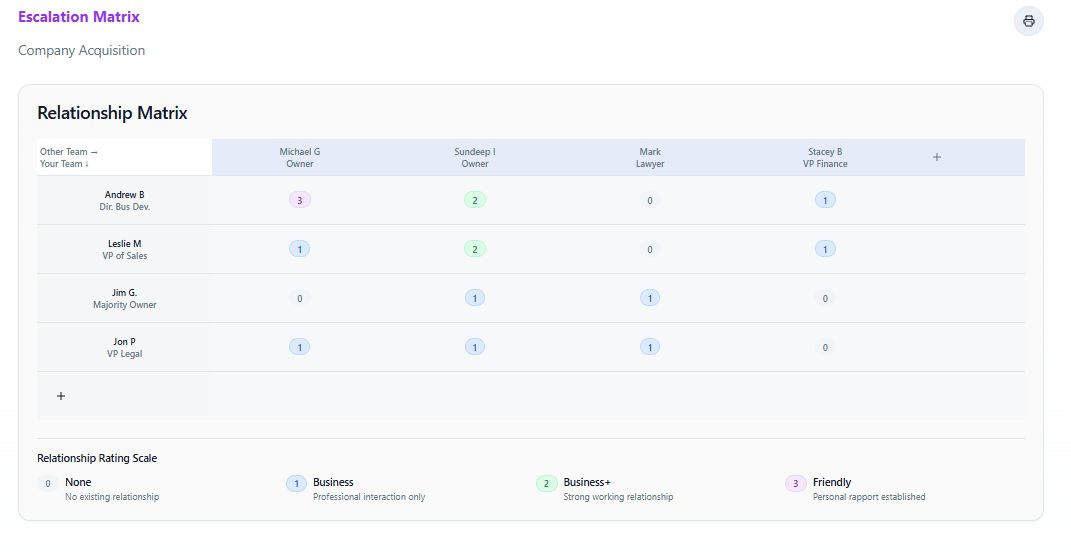

Step 1: map the people with a relationship matrix

Figure: Relationship Matrix for a company acquisition negotiation. The matrix maps relationship strength between your team (rows) and the other side (columns) using a 0-3 scale: 0 = None, 1 = Business, 2 = Business+, 3 = Friendly. Zeros reveal escalation gaps that require proactive relationship building.

The first step in the Ultimate Negotiation Strategy planning flow operationalizes the People component: mapping who can talk to whom and where escalation gaps exist.

In practice, the team builds a relationship matrix:

- Rows represent key players on your side.

- Columns represent key players on the other side (or across multiple counterparties).

- Each cell captures the strength of the existing relationship between those two individuals.

A simple four‑level scale works well, for example:

| Score | Meaning | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | None | No existing relationship |

| 1 | Business | Basic professional interaction only |

| 2 | Business+ | Strong working relationship, multiple positive interactions |

| 3 | Friendly | Personal rapport beyond business |

The goal is not to ensure everyone has deep friendships. The point is to identify where no relationship exists—the zeros—so escalation paths do not dead‑end when you need them most.

A relationship score of 1 or higher is usually workable for escalation, especially if supported by the right process and framing. What kills escalation is discovering mid‑crisis that your CFO has never spoken to their CFO, and neither knows who should make the call.

Where the matrix shows zeros at critical nodes, leaders can design pre‑negotiation actions:

- Host meet‑and‑greets, dinners, or site visits.

- Use charitable events, advisory boards, or joint working groups to create legitimate pretexts for interaction.

- Engineer introductions so that if escalation becomes necessary later, it feels natural rather than desperate.

This is power building through relationship design, not schmoozing.

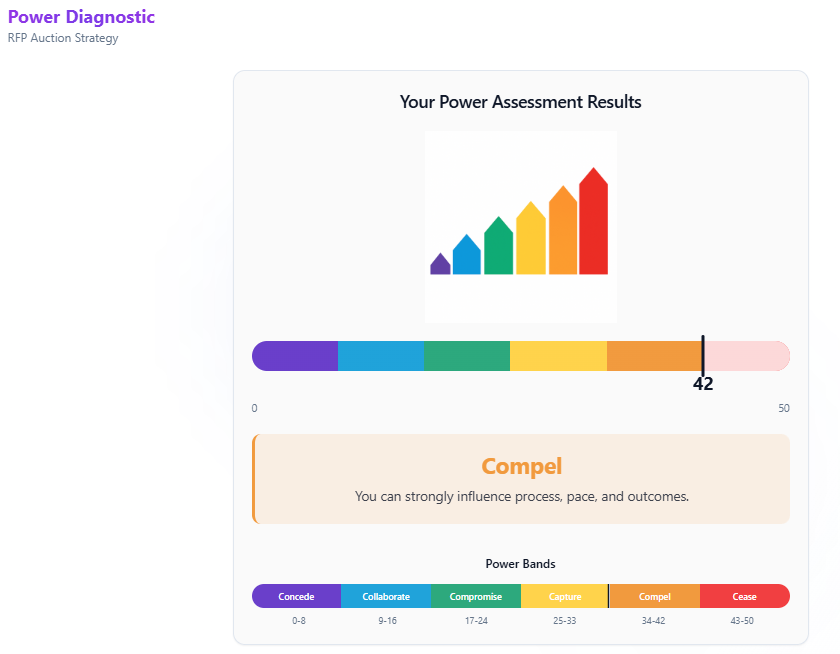

Step 2: diagnose power before choosing a phase

Once the people map is visible, the next step is to run a power diagnostic—a structured assessment that scores each side across the major sources of leverage.

Figure: Power Diagnostic output for an RFP Auction Strategy. The assessment scores negotiating power across Time, Options, and Circumstance dimensions, placing the buyer at 26 out of 50—in the “Capture” band. This score indicates sufficient leverage to run structured auctions and dictate process terms, validating the aggressive phase plan shown elsewhere in the article.

The three categories of power: Time, Options, Circumstance

Rather than treating power as a single abstract concept, the diagnostic organizes leverage into three practical categories:

Time

Who is under more deadline pressure? Time power flows to the side that can wait, pivot, or operate without urgency.

Typical questions:

- Do we have a hard contract expiration or regulatory deadline?

- Are they under board pressure to close deals this quarter?

- Can we create shared deadlines that reset the time equation?

Options (BATNA)

What alternatives does each side have? Options power comes from credible substitutes, walk‑away scenarios, or fallback plans.

Typical questions:

- How credible is our walk‑away alternative?

- How many qualified competitors do they have access to?

- Can we develop a second‑choice supplier or customer to increase our leverage?

Circumstance

This is where most strategic effort concentrates, because circumstance power is often hidden and highly contextual. A helpful framing question is: “Is there anything currently causing the other side to be more desperate?”

Circumstance includes:

- Their dependency – How replaceable are you in their eyes?

- Information power – How well do you understand their constraints, internal priorities, and decision process?

- Legitimacy and standards – Which benchmarks, laws, or norms favor your position?

- Relationship & reputation – What does your track record with them enable or constrain?

Desperation can take many forms: a competitor threatening their market share, a CEO mandate to cut costs, internal political pressure to show results, or operational pain that worsens each month. When you identify those conditions early, you can shape proposals and timing to align with their urgency rather than collide with it.

What the diagnostic produces

The output is not a single pass/fail score; it is a map of where you can already act strongly and where you must invest to build power. For example, a diagnostic might show:

- Strong legitimacy and good circumstance (they are desperate to solve an outage problem), but weak alternatives.

- Good relationships, but poor information on internal politics and decision authority.

From a strategic standpoint, each gap becomes a to‑do list: build alternatives, gather better information, create time pressure, or deepen relationships.

Only after running this diagnostic does it make sense to choose which of the 6 Cs you can realistically occupy at the start of the negotiation.

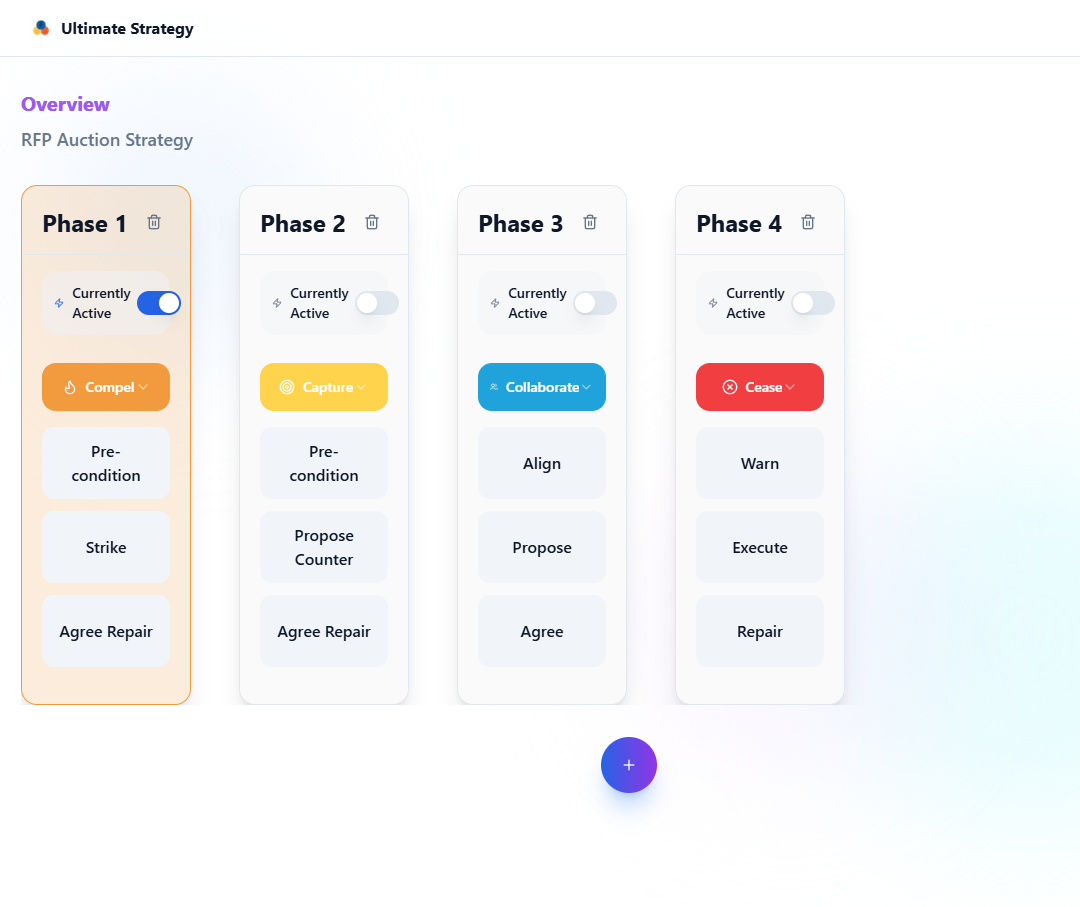

Step 3: plan your phases before you start

With people mapped and power diagnosed, you can now design a phase plan—a deliberate path through the 6 Cs rather than an improvised emotional journey.

Figure: RFP Auction Strategy Phase Overview – a four‑phase plan from Compel to Cease.

In the Ultimate Negotiation Strategy app, this appears as a Phase Overview:

- Phase 1: your initial power posture.

- Phase 2: what you do if Phase 1 does not work.

- Phase 3: where you escalate or de‑escalate next.

- Optional later phases, including Cease.

For each phase, you specify:

- Which power phase (Concede through Cease) you are in.

- Which style on the wheel you will use in that phase.

- The high‑level intent (e.g., “shape value,” “structure give‑gets,” “signal walk‑away boundary”).

The key discipline is to ask, in advance:

- If Collaboration fails, do we escalate to Compromise, Capture, or Compel?

- Under what conditions will we not escalate further and instead Cease?

This planning step removes a huge amount of emotional volatility. When a counterpart refuses a reasonable proposal, your team is not asking “what do we do now?”; it is executing the next phase it already designed.

Step 4: define objective triggers for movement

A phase plan only works if the team knows when to move from one phase to the next. That requires triggers: observable conditions, not feelings.

Good triggers might include:

- A deadline passes without required approvals.

- A counterpart formally rejects defined guardrails or minimum terms.

- An internal risk committee refuses to clear a proposal after a set number of revisions.

Each trigger is agreed in advance and logged with the phase plan. When it fires, the team does not debate whether they are “overreacting”; they simply move into the next planned phase with the associated style.

This is how process protects power: it prevents premature escalation while also preventing endless, unbounded compromise.

Step 5: translate strategy into an execution plan

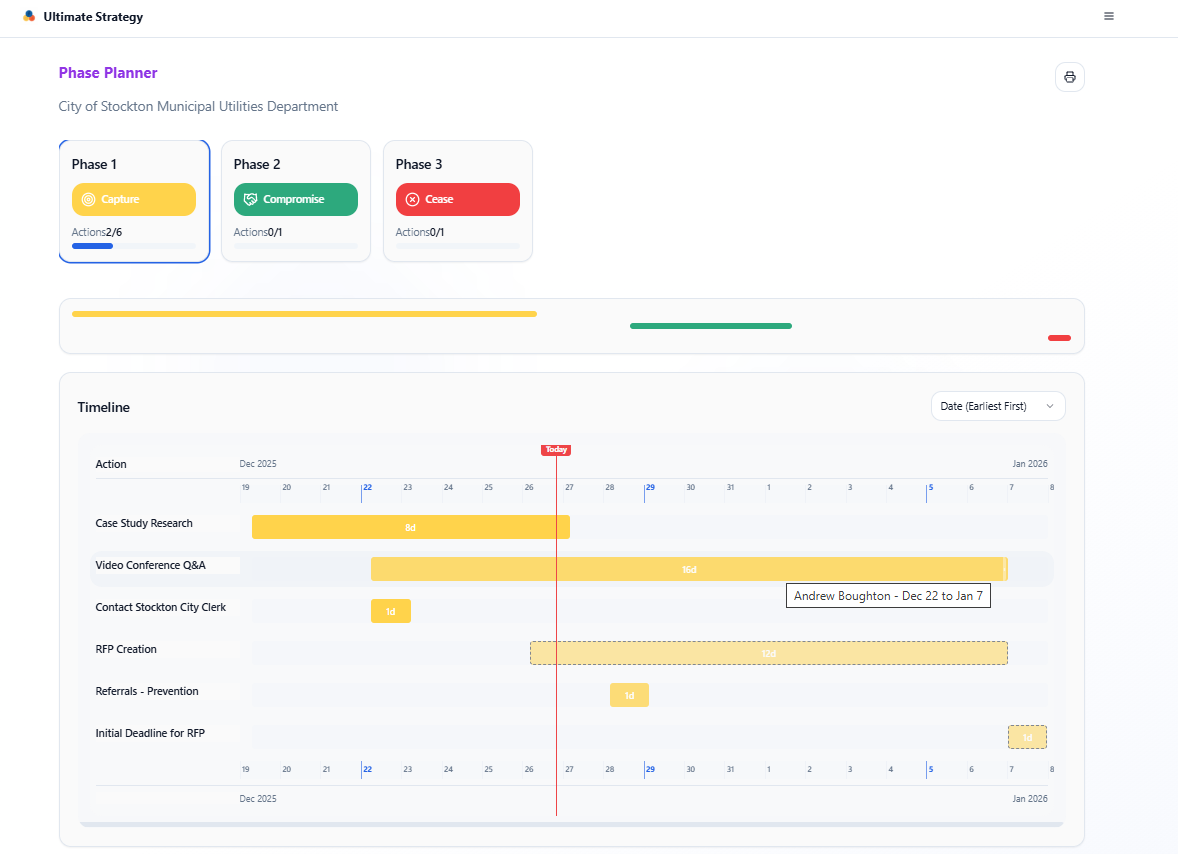

At this point the models are set, but the work still needs to be run. That is where the Phase Planner comes in.

Figure: Phase Planner output showing timeline and action assignments across three negotiation phases.

In practice, the Phase Planner turns strategy into a timeline of concrete actions:

- Relationship‑building steps tied to specific dates and owners.

- Information‑gathering tasks and interviews.

- Internal alignment meetings with legal, finance, or operations.

- External milestones such as RFP releases, bid deadlines, or auction dates.

Visually, this often looks like a Gantt chart with each phase represented as a band, showing when specific actions must occur for the strategy to work. Leaders can see at a glance whether:

- The plan is front‑loaded with power‑building tasks before critical deadlines.

- Enough room exists for repair steps if a phase fails and you need to reset.

- The team is over‑relying on a single executive to execute multiple actions simultaneously.

When used rigorously, the planner converts what would otherwise be a loose “strategy deck” into an operational schedule.

The RFP auction strategy: when buyers hold the power

One of the clearest illustrations of the framework is a modern reverse‑auction RFP process for selecting a SaaS provider. In many such events, procurement holds significant structural power: they control access, timing, and the rules of the game.

Using the models above, a high‑power buyer might design phases like:

- Phase 1 – Compel (Auction style): Vendors are invited into a tightly defined reverse auction with standardized requirements and transparent rules.

- Phase 2 – Capture (Hard bargaining / Concession trading): After the auction, shortlisted suppliers enter structured negotiations on terms, risk allocation, and service levels.

- Phase 3 – Collaborate (Win‑Win / High dependency for the winner): Once the preferred supplier is selected, the tone shifts toward co‑designing implementation, success metrics, and ongoing governance.

Throughout, the buyer’s ability to Cease—to award no contract or re‑run the event—remains explicit in the background, giving credibility to Compel and Capture.

What makes this three‑dimensional is not the auction itself, but the way the buyer:

- Maps decision makers across internal IT, security, finance, and operations.

- Designs power‑building steps in advance (for example, testing the market to ensure genuine alternatives).

- Uses process to protect relationships even while applying intense price pressure.

When done well, suppliers experience the process as tough but fair, because the rules and phases are transparent and the collaborative phase at the end is genuine.

Using the wheel safely: earning the right to style

With all of these pieces in place, the Wheel of Negotiation becomes what it was designed to be: a menu of earned behaviors, not a set of personality choices.

For example:

- If diagnostics and phase planning say you are in Capture, you can run hard‑bargaining meetings, use sharp anchors, and trade limited concessions without being reckless, because the system can sustain that posture.

- If you are in Collaborate, you design joint working sessions, problem‑solving workshops, and transparent information sharing—but you do so with a clear understanding of how far you can go before you must protect your floor.

In other words, the wheel is where discipline meets skill. Good negotiators still need to ask sharp questions, frame value, and manage emotion; the system around them simply ensures that those skills are deployed in a way that is structurally sound.

How to start applying this in your organization

For most teams, the first step is not to adopt every component at once but to introduce three disciplines:

- Run a People map before your next major negotiation. Build a simple relationship matrix for both sides and identify gaps. If you do nothing else, this will change how you think about escalation.

- Choose a starting power phase deliberately. Before the first meeting, force the team to answer: are we in Concede, Collaborate, Compromise, Capture, or Compel—and why?

- Write down at least four triggers. Define four specific conditions that will move you to the next phase, whether that means escalating or choosing to de-escalate your use of power.

You are effectively planning Phase 1. Fill out the details as much as you can. When you hit a trigger, then it’s time to begin planning out the next phase and the details associated with it. Once those habits are in place, you can layer in the full planning flow and integrate into your training and deal reviews.

Frequently asked questions

1. How is this different from traditional negotiation training?

Most negotiation training focuses on individual skills—active listening, framing, anchoring, and concession tactics. The Ultimate Negotiation Strategy sits above those skills and answers the question: “Which style should we use, and do we have the power to sustain it?” Traditional training assumes you already know the answer; this framework helps you design the right answer before the first meeting.

2. Do I need to use all three models for every negotiation?

No. For straightforward, one‑on‑one deals with clear power dynamics, the Wheel of Negotiation alone may be sufficient. The full People–Power–Process architecture and phase planning become essential when deals involve multiple parties, internal and external stakeholders, or high political or financial risk.

3. What if the other side does not follow a process or plan?

That is precisely why you need one. When counterparts are reactive, emotional, or disorganized, a well‑designed process gives you control of timing, sequencing, and escalation. You are not hoping they will cooperate; you are building a system that works even when they do not.

4. Can this framework be used for internal negotiations, such as budget or resource allocation?

Yes. Internal negotiations often involve more stakeholders and more interdependencies than external deals, making the People–Power–Process model especially valuable. The relationship matrix helps you map decision makers and influencers across departments, and the power diagnostic reveals whether you need executive sponsorship or better data before pushing for resources.

5. How long does it take to build a full phase plan?

For a major deal—an RFP, M&A transaction, or enterprise contract—expect to invest 4–8 hours of team time to build the initial People map, run the power diagnostic, and design a three‑ or four‑phase plan with triggers. That investment typically saves weeks of thrashing and prevents costly missteps during execution.

6. What happens if we start in the wrong power phase?

The phase plan is designed to be adaptive. If you start in Collaborate but quickly realize you do not have the power to sustain it, your pre‑defined triggers will move you into Compromise or Concede without a politicized internal debate. The key is to recognize the mismatch early and adjust, rather than hoping the situation will improve on its own.

7. Is this only for buyers, or can sellers use it too?

Both. Buyers and procurement teams often use the framework to design reverse auctions and structured RFPs where they hold significant power. Sellers and business development teams use it to diagnose where they actually sit on the power spectrum and to build leverage before entering high‑stakes negotiations.

8. How do I handle negotiations where the other side has significantly more power?

When you are in a low‑power position, the honest answer is often to start in Concede or Collaborate and invest heavily in power‑building activities—developing alternatives, gathering better information, creating time flexibility, or deepening relationships—so you can move up to Compromise or Capture in a future round. The framework does not pretend you have power you lack; it shows you how to build it systematically.

9. Can this framework integrate with existing CRM or project management tools?

Yes. The relationship matrix can be built in Excel or embedded in your CRM as custom fields. The Phase Planner output is essentially a Gantt chart and can be imported into tools like Microsoft Project, Asana, or Monday.com. The Ultimate Negotiation Strategy app is designed to export data in standard formats for integration.

10. What is the biggest mistake leaders make when adopting this framework?

The most common error is skipping the power diagnostic and jumping directly to phase planning. Teams choose a collaborative or assertive style based on preference or personality rather than evidence, then wonder why execution fails. The diagnostic is not optional; it is the foundation that makes every other step realistic and sustainable.

References and Sources

- Google Search Central. (2025). “Creating Helpful, Reliable, People-First Content.” https://developers.google.com/search/docs/fundamentals/creating-helpful-content

- Backlinko. (2025). “Google E-E-A-T: How to Create People-First Content.” https://backlinko.com/google-e-e-a-t

- Workshop Digital. (2024). “An SEO Guide to E-E-A-T.” https://www.workshopdigital.com/blog/googles-e-e-a-t-and-seo-guidelines/

- Stellar Content. (2025). “The Complete Guide to Google E-E-A-T: How to Improve SEO.” https://www.stellarcontent.com/blog/seo/the-complete-guide-to-google-e-a-t-what-is-it-why-is-it-and-how-do-you-create-it/

- Logical Position. (2024). “How To Boost SEO and Engage Users with Long-Form Content.” https://www.logicalposition.com/blog/how-to-boost-seo-and-engage-users-with-long-form-content

- Sangfroid Web Design. (2025). “How to Write an SEO-Friendly Author Bio for E-E-A-T.” https://www.sangfroidwebdesign.com/website-quality/seo-friendly-professional-author-bio-eat/

- Seota. (2023). “How Google EEAT Can Take B2B Content From Boring To Great.” https://seota.com/b2b/how-google-eeat-can-take-b2b-content-from-boring-to-great/

- Altitude Marketing. (2024). “Why E-E-A-T Still Matters in B2B SEO & How to Establish It.” https://altitudemarketing.com/blog/eeat-b2b-seo-guide/

- TripleDart. (2025). “How Google E-E-A-T Can Enrich Your B2B Content.” https://www.tripledart.com/b2b-seo/google-eeat

- Ezi Gold. (2025). “Use Thought Leadership for E-E-A-T Signals: A Guide to Expertise.” https://ezi.gold/use-thought-leadership-for-e-e-a-t-signals-a-guide-to-expertise/

- Search Engine Land. (2025). “Thought Leadership Content: Build Authority & Trust.” https://searchengineland.com/guide/thought-leadership-content

- Salesgenie. (2025). “B2B Sales Negotiation Tactics That Win More Deals.” https://www.salesgenie.com/blog/b2b-sales-negotiation/

- LinkedIn. (2024). “Mastering Reverse Auction Negotiations: A Guide for Modern Procurement.” https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/mastering-reverse-auction-negotiations-guide-modern-procurement-vr-2gzsf

- Art of Procurement. (2025). “Auctions in Procurement: My Proven Way to Conduct RFx Events.” https://artofprocurement.com/blog/auctions-in-procurement

- Simon-Kucher. (2024). “Mastering B2B sales negotiations: Essential best practices for success.” https://www.simon-kucher.com/en/insights/mastering-b2b-sales-negotiations-essential-best-practices-success

- Apriori. (2025). “When should buyers and procurement teams use reverse auctions?” https://www.apriori.com/blog/what-is-a-reverse-auction-how-buyers-maximize-strategy/

- Go Juggernaut. (2025). “E-E-A-T signals that AI systems consume: building author trust.” https://gojuggernaut.com/blog/e-e-a-t-signals-that-ai-systems-consume-building-author-trust-expertise/

- Aligned Negotiation. “Mastering the Bargaining Range (ZOPA) in B2B Negotiations.” https://www.alignednegotiation.com/zopa-bargaining-range

Note: This article also draws from the author’s proprietary Ultimate Negotiation Strategy framework and app, developed through direct practice in enterprise negotiations, municipal procurement, and strategic partnership design.